Episode 8.5: The Dwarves, The Dragon, and the Welsh

- James Hedrick

- Jul 7, 2025

- 12 min read

Welcome back to Something About Dragons! Here's my sincere hope that none of you have been magically transformed into animals since our last installment and forced to produce incestuous offspring. Welsh mythology, ladies and gentlemen.

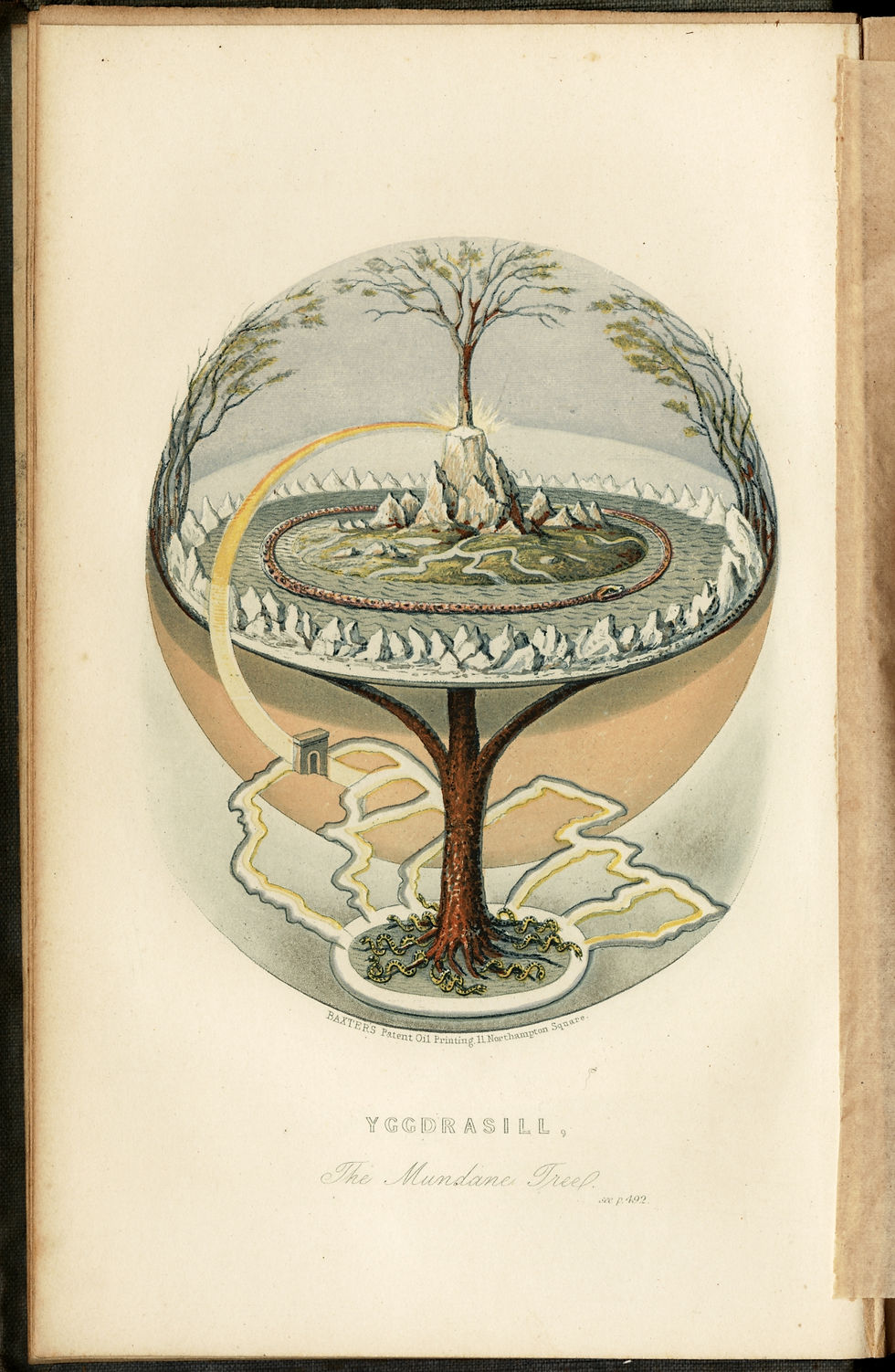

To get back into it, while The Virgin and the Swine give us an example of how mythology and epic can directly influence modern genre fiction (and the weirdness that can ensue), The Hobbit gives us a good example of how modern fantasy will most frequently use ancient myth. Not just because it’s Tolkien and endlessly borrowed. But because it takes elements of mythology – the aforementioned theft of the cup from Beowulf, the dwarves (not dwarfs, Tolkien was very specific about that) of Nordic legends, a little Poetic Edda here, a little Kalevala there, etc. – and infuses it with the modern “romances.” The Hobbit also incorporates many of the concerns of a rapidly capital-M Modernizing world that are wholly divorced from the specific times and cultures that produced the original myths. The Prose Edda isn't particularly concerned with deforestation, after all.

Stir that together and BAM! Modern fantasy as a genre! This is a concept of mythology as toolbox, to mix in another metaphor. Mythology is mined for meaningful symbolism.

Maria Nikolajeva calls these building blocks fantasemes in her 1988 book The Magic Code: The Use of Magical Patterns in Fantasy for Children. Fantasemes are the motifs, the “irreducible but replicable chunks of fantastic worldbuilding”, as Brian Attenby defines them in his 2022 book, Fantasy: How It Works. Mythology is adapted as literary building blocks for modern stories but doesn’t represent in any real way an unbroken line of descent from the Epic of Gilgamesh. These are basic building blocks of fantastic stories – think the prophesized savior, the inscrutable wizard, the JourneyQuest.

The key is that all of the modern fantasy genre, even the early 20th century stuff we’ve been discussing and the 19th century predecessors, is all post-Enlightenment, post-Scientific Revolution, post-Empiricism fiction. Now, there are mountains of books on all those subjects and many, MANY arguments to be made about the validity, applicability, and influence of Empiricism or the Scientific Revolution on awful things like eugenics, colonialism, etc. Which is all largely true. But this is not a history of science or philosophy project. For that, I recommend you listen to the podcast, The History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps; it’s really good.

Suffice to say that these modern fantasy genre books and authors may be evoking the Otherworld or an earlier, more romantic period. They are writing, however, in a time where heliocentrism, the scientific method, the Reformation, and Pasteurization are all generally accepted. Again, so are bananas ideas like phrenology, but, because we’re post scientific revolution, fantastic stories are now obviously FANTASTIC, obviously fictional. Stories ostensibly written as entertainment and sold for money. Not as, you know, the fundamental expression of an entire culture’s cosmology.

Just to beat this dead horse one more time, Pliny the Elder, back in the early first century, wrote about dragons and griffins and dog-headed men and sciapods (one-footed dwarves, look’em up) in his Naturalis Historia as real things. Now, yes, fantastic ancient stuff always lived “over there”, away from civilization. In Pliny’s case, beyond the range of Rome or whatever hegemonic culture exerted control. “Here be dragons” at the edge of the map and all thar.

But the fantasticism of the mythology was more or less accepted as true. The Illiad, Beowulf, Gilgamesh, the Rig Veda, the Kalevala, other cultural epics I’m too Eurocentric to bring immediately to mind – these cultures had different relationships to these fantastic tales than we do to, say, Walton’s The Virgin and the Swine. Our relationship to that story – and, by extension, other genre fiction – is much different that an 11th century Welsh soldier was to the Mabinogion. So different that I have trouble thinking of a modern parallel beyond maybe the relationship of the Puritans to the Bible.

And it isn’t entirely because of the commodification of this literature via capitalism. To ancient cultures or societies, the epic tales were real or true, in a way very different from how we view modern genre literature. Fantasy does different things for us – such as Tolkien’s escapism, recovery, and consolation from On Fairy Stories – than epics and mythology did for ancient people. Ancient people obviously understood the metaphorical nature of the story of, say, Odysseus, but they’re relationship to the truths from the story were different than the “truths” – the understanding, the insight – that a modern reader might gain from, say, the Lord of the Rings. Modern readers fundamentally have a different relationship to our modern fantasy genre than ancient peoples did to their mythoi. Different motivation, different engagement with the text, etc.[1]

This is what we mean when we say, “The past is a foreign country.”

Ok, having spent a few thousand words beating that dead horse, let’s talk about a few other aspects of The Virgin & the Swine and The Hobbit.

First, feminism. The Virgin & the Swine (and, by extension, the Mabinogion) is very concerned with the transition from a structure of matrilineal descent to one of patrilineal descent. Gwydion (the protagonist) is Math’s (the current King) heir because Gwydion is Math’s nephew (Math’s sister’s son). Matrilineal decent represents the only way to be sure of a familial blood connection in Iron Age Wales. The incoming, pig-having migrants are the ones who believe in “fatherhood,” something Walton never uses to subtly question the existing misogynistic ideas of mid-20th century American culture. wink, wink, nudge, nudge

Similarly, all Gwydion’s machinations are based on getting his sister – and affirmed “virgin” with whom he has an incestuous sexual relationship – to produce him an heir, Llew. By the time Llew is of age, one-man one-woman marriage has more or less taken hold. Unfortunately, due to some pretty horrible curses laid on Llew by his mother Arianhod, Llew can’t marry anyone, and his wife (Blodeuwedd, a human wife constructed from leaves and flowers by Math and Gwydion, and about whom a reasonable review of Walton's book would have much more to say) is dead.

Similar to CL Moore, Walton’s writing contains some very feminist themes addressing “modern” concerns of women through a fantastic lens. She uses the Mabinogion story to highlight the social structures that bind women and frame the subversive actions that women leverage to attempt to carve out a bit of self-determination for themselves. More broadly, Walton writes about the restrictions of women within patriarchal societies and relationships, the slow accumulation of these restrictions, and how the limits of behavior within patriarchal societies force the hands of women. Patriarchy is limiting, and, therefore, characters like Arianrhod and Blodeuwedd are in a sense forced to take drastic measures (e.g., curses, murder) because no other options are available to them within the social structure. For example, Arianrhod’s only outlet for regaining her sense of self and self-determination is to work some pretty horrific magical vengeance on Gwydion’s dumb, controlling, manipulative ass.

And that, I think is the crux of Walton’s feminist themes here. The men in the story, the protagonists, especially Gwydion but also Math and Goronwy, are thoughtless, controlling, and acting without concern for the effects of their actions on any of the female characters. It’s telling that Pryderi Pig-Bringer - whom Gwydion tricked, stole from, and mocked - gets an epic battle and respect after death (see photo below). On the other hand, Gwydion, Llew, and Math remain absolutely baffled by the anger and reaction of Arianrhod and Blodeuwedd to their constant meddling in their lives. Arianrhod is just minding her own business throughout the whole story, and Gwydion just will not Let It Go.

Arianrhod (and Blodeuwedd) also react very similarly to the male protagonists of the story – at least Blodeuwedd acts from similar motivations and desires – but are seen by the various male Welsh semi-deities as baffling and inscrutable. Social constraints on women continue to tighten and become more restrictive throughout the story. This forces Arianrhod and Blodeuwedd to take some drastic measures – curses, murder plots – to ensure some self-determination. Their behavior is almost as drastic as, say, creating a bride for Llew out of flowers and whatnot with no thought to the desires of the sentient construct. Life probably would have been better for everyone if Arianrhod could have just challenged Gwydion to a duel or something. But she couldn’t. Because sexism.

There’s much, much more to be said about Walton’s feminist themes here, and we’ll pick up more thoroughly on this thread of the genre from Walton and Moore when we get into the late 60’s and some of the folks like Le Guin, McCaffrey, and others. I highly recommend a close reading of The Virgin and the Swine for these themes, and remember this is a book adapted in the mid-1930’s from an 11th-ish century Welsh myth working with feminist themes not unlike those you might see today.

Ok, we haven't said all that much about The Hobbit yet. Umm…just go read The Hobbit? I’m not a “canon” guy, but that’s as close to a requirement as you’re going to get. It’s a couple hundred pages, it’s quick, it’s super fun. And, it’s the first book as part of this process (excepting some Clark Ashton Smith stories) that I basically have memorized. Not word for word, obviously, but phrases, sentences, whole passages, just come back as I read them. It’s one of the most…comforting books to me personally, so it was interesting for me to read it primarily as an analytical exercise.

First issue to address, Tolkien is a better structural writer than I think he gets credit for. Or, at least, his ability to craft a story is often overshadowed by his worldbuilding and general Mt. Fuji-ness within the genre. He uses Bilbo very deftly as the audience surrogate, moving him through the world and letting us get the exposition we need through his eyes. Consider what we learn from hearing the dwarves singing (there's a huge world out there with monsters and magic in it), or reading off-hand references to lending other hobbits money (the Shire has a well developed, stratified local economy), or why you don’t pick trolls’ pockets (because they might have singing keys in them who'll sell you out).

Also, Tolkien writes real character growth for Bilbo. Bilbo slowly adapts and changes as the adventures go on. I honestly think that’s why the film adaptations didn’t work quite as well as The Lord of the Rings. That and studio interference and a last-minute directorial change.

Bilbo is really the only dynamic, rounded character in the story. The dwarves, even Gandalf, are fairly static, and the dwarves barely have any distinguishing features (Thorin is a scion, Bombour is fat, Oin and Gloin…start fires good?). Which isn’t bad. It’s not their story. But the movies had to add something to make them distinguishable – so much that Kili got a love story shoehorned in there.

This literary aspect – character growth – is where you see Tolkien really diverge from earlier authors he’s obviously borrowing from, like Dunsany or MacDonald. Those stories, like The King of Elfland's Daughter or even Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, are plot-driven or even dreamlike. Less so with Mirralees – Nathaniel Chanticleer has a hell of a character arc, not a million miles away from Bilbo’s actually – but these early fantasy or “romance” books tend to be less concerned with the interiority of the characters or their overall development. Characters tend to be unidimensional (or flat/cardboard/etc.) and exist to move the story along. For example, Lirazel in TKED changes her mind about where she wants to live, but we don’t really dwell on the why or the how. She’s from the Otherworld, she misses it, she leaves, Alveric quests to find her. There’s the metaphorical implication that the Otherworld simply can’t exist long-term in “the fields we know”, foreshadowing the eventual resolution of the plot, but her essential character doesn’t change.

Other examples abound. In Eddison, the characters are barely more than Hero! The pulps work really hard to keep their recurring characters from changing all that much. I’m just going to ignore whatever happened in A Voyage to Arcturus. But, essentially, in most of these previous stories, individual characters aren’t really altered or changed that much by their experience. They have simple, easily understandable motivations, and, while the world is changed by their actions, as the characters bounce off each other, the characters themselves change very little. You see something similar in Walton’s writing, as well.

But Tolkien, despite his real desire to evoke these past storytelling forms, is strongly mixing more capital-M modernist themes and ideas into his work, with Bilbo becoming a different person at the end of the book than he was at the start of it. That’s the story we’re following. Bilbo’s growth – or at least change – from a humble burger with a buried Tookish bent to, at the beginning of The Lord of the Rings, an eccentric millionaire who contributes to the delinquency of minors. And who also serves as the spark to the awakening of the stagnant Shire, but I think Tolkien was always a bit conflicted about that message.

Finally, and I only want to touch on this briefly because we'll come back to it, The Hobbit really establishes the full independent secondary world as the standard for fantasy. Many of the earlier “settings” are somehow connected to our world and universe.[2] It’s a voyage to Arcturus, an actual star system. House on the Borderland takes place in Ireland. The King of Elfland's Daughter is a fictionalized place on Earth, though more dreamlike than anything else. Jirel lives in France. The Hyborian Age is far past Earth. The Wind in the Willows takes place in some form of England, though the River is unspecified. My money is on the Thames. Dorothy goes from Kansas to OZ, then returns. Even The Worm Oroborous, probably the closest to a separate, independent secondary world, ostensibly takes place on Mercury. Time and the Gods and Gods of Pegana are the two early examples that really go whole hog on the fictional world without connection to our own, along with Mirrlees’ Lud-in-the-Mist.

But Tolkien ditches the training wheels. It is true that early in the drafting process, Tolkien considered having Middle-Earth (or Arda, which would be the whole world) as a past version of Earth. And The Hobbit intro does refer to big people clomping around “these days” and scaring all the Hobbitses, but by the time of LOTR, etc., Tolkien refers to Middle-Earth in a BBC interview in 1971 as not the world we live in, but possibly Earth at a “different stage of imagination”. Or another level of the Tower, as Stephen King might say.

More importantly though, other than the pseudo framing structure of the narrator, The Hobbit doesn’t rely on references or links to the “real world” to establish the reality of the secondary world. Howard wrote a story bible for the Hyborian Age to flesh out his far past world. Again, The Worm Ouroboros is ostensibly on Mercury. Lots of CAS is in Zothique, a far future location.

Middle-Earth simply is a different place. A different location. Like the Undying Lands after the destruction of Numenor, you can’t get there from here. Tolkien largely gets away with this by having Bilbo look an awful lot like a rural English gentleman – and the Shire look an awful lot like the rural English countryside – and having him serve as an audience surrogate, minimizing the need for substantive connection to the real world.

It’s hard to undersell how influential this is. It’s not fully formed, not until LOTR really, but Tolkien is showing that people will come along for the ride in a completely different world. He’s taking the lessons from On Fairy Stories and truly embracing them. As people, we need recovery, consolation, and escape from our world, and, as readers, we’ll happily find it in fantasy worlds untethered from our own.

I’m going to have more to say about The Hobbit, but mostly in relation to other books in the future. It really is a foundational text, but we’ll leave it there for now. There’s just a ton more that could be said about The Hobbit, but I think others have said it better and more extensively than I can in the time remaining, so I’ll stick to what I think is important for the future development of the genre.

So, in the last two installments, we covered Evangeline Walton’s mythical retelling of the Welsh Mabinagion and discussed how mythology mostly provided raw materials for modern authors to work with, allowing them to address modern day topics in a fantastical form, rather than being the straight-line continuation of various oral and mythological traditions. Authors are mining for content, not serving as modern day Homers. We also addressed feminist themes and issues being covered within a fantastical, mythological structure, updating and adapting a mythological work to center it within contemporary discussions of feminism. We also discussed some of the specific contributions to the genre of Tolkien’s The Hobbit, most especially how it moved the genre closer to embracing the fully separated, fully independent secondary world, untethered (mostly) from the fields we know.

That’s enough for today. Join me next time as we dive back into the pulps with Fritz Lieber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser and welcome onto the stage a couple names more often associated with the sci-fi side of speculative fiction: Fletcher Pratt and the L. Sprague de Camp.

[1] There is a whole literature on Platonist philosophy, the “One”, and even early Aristotelianism that contradicts a universal religious acceptance of, say, the ancient Greek pantheon. Ancient societies fantasy authors are ransacking for fantasemes weren’t any more monolithic than ours. There were diverse views regarding the nature of the divine. There were dissidents, fanatical adherents, and probably decent mass of whatever the equivalent of Christmas/Easter churchgoers was. But again, not a philosophy project.

[2] I use setting here for lack of a better term – “story worlds” is probably a better descriptor and the term frequently used by Attenby and others.

Comments