Episode 3: Tarzan the Incel or Beaten to a Pulp

- James Hedrick

- Apr 30, 2025

- 12 min read

Welcome to Episode 3 of Something About Dragons, with this week’s episode entitled “Tarzan the Incel” or “Beaten to A Pulp.” I couldn’t decide.

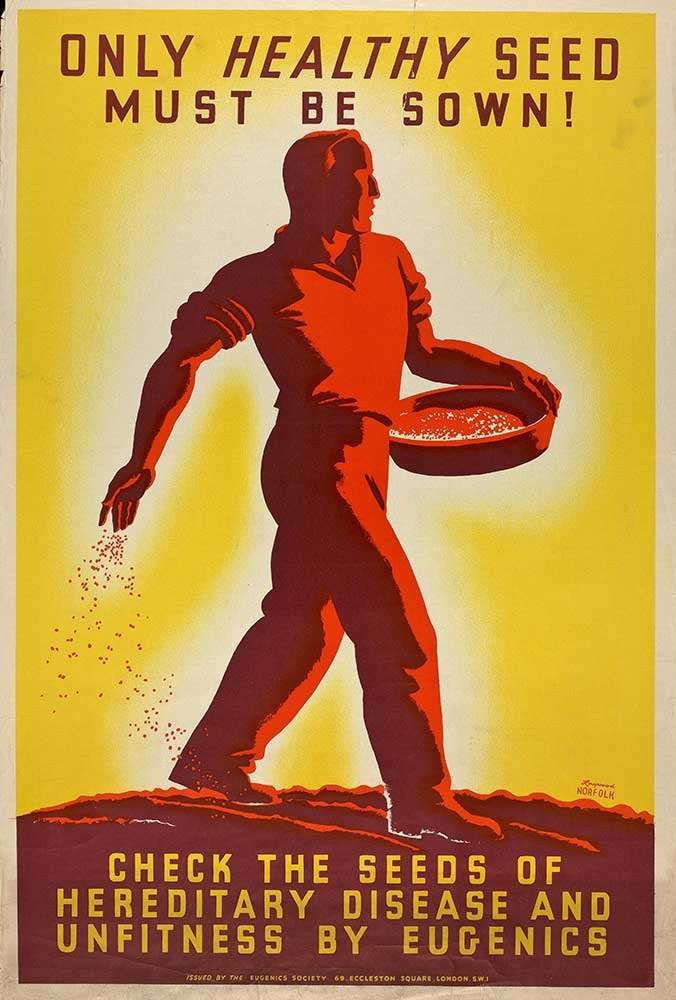

A quick content alert for readers. This installment deals quite a bit with eugenics and racism. Both topics are discussed in reference to the beliefs of the author of Tarzan, Edgar R. Burroughs, and the fictional actions of Tarzan, the character. If that might upset or disturb you - and it is fairly gnarly - you might want to skip to our discussion of A Voyage to Arcturus in the next post.

In my original draft of this post, I was going to say that this installment was a lot like both the first two installments in this project, with one broadly famous story contrasted against a more obscure, but highly influential piece. Another pairing of children's literature - though Tarzan is more indebted to 19th century adventure fiction, a la Kipling, and foreshadows more young adult literature - paired with an influential-but-obscure piece. And, at the surface level, that’s what we have. Tarzan of the Apes is a famous book – or, rather, Tarzan is a famous character – and A Voyage to Arcturus, the other book covered in this week’s post, is best described as a philosophical work of space fantasy that sets up a lot of post-WWII, mid-century space fantasy, like Dune, The Book of Ptath, Dying Earth, even Star Trek. Seriously, if you read A Voyage to Arcturus, you’ll see a LOT of influence on Star Trek – the plot as thinly-veiled philosophical discussion, for example.

I had also considered reinforcing a topic that has come up in the last two episodes: adaptations. The idea that we see in Oz, in The Wind in the Willows, and Tarzan is: what translates to new mediums, survives. A Voyage to Arcturus really breaks some new ground and has influenced authors from C.S. Lewis to Harold Bloom to James SA Corey (a two-fer, for those in the know). But, while everybody knows who Tarzan is, David Lindsay’s “Maskull” from A Voyage to Arcturus isn’t exactly a household name, though A Voyage to Arcturus did get a review in the Washington Post in 2021.

I thought about discussing the Man vs. Nature themes. I thought about comparing and contrasting the cultural sensations of Oz and Tarzan. There’s a real transition from “children’s literature” to “boys” or “juvenile” fiction with Burroughs, which had a major influence later with mid-century science fiction writers, Heinlein being the most prominent example.

I thought about linking the discussion of adaptations to how Burroughs was one of the first writers to incorporate. I thought about skipping Tarzan entirely – Burroughs’s most famous work – because, while discussing the early history of the fantasy and speculative fiction genres requires talking about Burroughs, there are other options. The Barsoom stories are an obvious example. Gary Gygax’s famous Appendix N from the first edition Dungeon Master’s guide doesn’t even list Tarzan, but recommends Burroughs’ Mars, Venus, and Pellucidar series. Honestly, Pellucidar is probably the most likely alternative – a “hollow earth” story with dinosaurs and megafauna. It’s pretty good, honestly, despite my personal aversion to hollow earth stories. Tarzan even makes an appearance in Pellucidar crossover entitled Tarzan at the Earth’s Core. I almost did that story as kind of a twofer and because it’s got airships and all that great Victorian-era Jules Verne stuff.

I thought about a lot of different ways to approach the influence of Tarzan on fantasy fiction. However, as I re-read Tarzan of the Apes for the first time in probably 25 years or so, I felt like I needed to go in a different direction.

So, let’s talk about eugenics.

Hooray! Let's delve into a light-hearted and sunny discussion of one of the 20th Century’s most horrendous and despicable ideologies! Which Burroughs specifically wrote Tarzan to embody. A quote from an essay Burroughs wrote in Writer’s Digest in the early ‘30’s. Quote:

"I was mainly interested in playing with the idea of a contest between heredity and environment. For this purpose I selected an infant child of a race strongly marked by hereditary characteristics of the finer and nobler sort, and at an age at which he could not have been influenced by association with creatures of his own kind I threw him into an environment as diametrically opposite that to which he had been born as I might conceive."

Quoted in John Taliaferro, Tarzan Forever: The Life of Edgar Rice Burroughs Creator of Tarzan, New York: Scribner, 1999, 14.

A few things to note here. One, Africa is “an environment as diametrically opposite” of European culture as Burroughs can conceive, and the explicit assumption here is that Tarzan survives and thrives because of his hereditary characteristics or “good stock”, a phrase repeated multiple times in Tarzan of the Apes.

To quote Burroughs again, from Tarzan of the Apes, Chapter VI: Jungle Battles:

In his veins, though, flowed the blood of the best of a race of mighty fighters…

That is certainly one way to describe the English.

And, let’s not forget, Tarzan is a character descended from the British Aristocracy, the group that the father of eugenics – Sir Francis Galton – thought was the pinnacle of human evolution up to that point, which explains why an American writer establishes Tarzan as an upper class British orphan of “good stock”. It’s eugenics all the way down.

There are almost countless other examples of racism and eugenics ideas in the book. Jane is almost always described as “a beautiful white woman.” Or, sometimes for variety, “white girl”. I counted at least three times in one chapter (chapter 18, for those interested). It’s very Greek. Homeric epithets, like describing Achilles as “swift footed”, but racist. Jane’s maid is also profoundly racist stereotype.

At one point in the book, a black native tribe moves into Tarzan’s range. They are described as “low and bestial” in appearance. “Savage” is frequently used as a descriptor. They also happen to be cannibals with their teeth filed to points, and Burroughs makes a point to comment on the size of their lips. In the text, it’s clear that they are being descriptively linked with Tarzan’s former Mangani ape tribe. It's obvious that Burroughs doesn’t just think that the Mangani ape tribe is “as diametrically opposite” to white British society as he could conceive, but Africa and black Africans in general.

Short aside, for a book (and a series) frequently described as “fast paced”, Burroughs certainly spends a lot of time with Tarzan tormenting the black native tribe that moved into his home range.

Furthermore, Tarzan introduces himself to the party of Jane with a note that says, in part,

This is the House of Tarzan, the killer of beasts and many black men.

“Tarzan” means “white-skinned” in the Mangani ape tongue, for crying out loud. The book is just saturated with racist language and descriptions.

The damn comic relief characters manage a drive-by racial stereotyping of Muslims while discussing the Spanish Reconquista.

The eugenics quotes just go on and on.

Insofar as Clayton was concerned, it was a very different matter, since the girl was not only of his own kind and race…– Chapter XV

The intelligence that was his by right of birth. – Chapter XIX

It was the hall-mark of his aristocratic birth, the natural outcropping of many generations of fine breeding, an hereditary instinct of graciousness which a lifetime of uncouth and savage training and environment could not eradicate. – Chapter XX

That last quote is in reference to why Tarzan didn’t sexually assault Jane after he saved her from Terkoz, the then leader of the Mangani, his former not-quite-gorilla tribe. And the chapter is entitled “Heredity”.

Notice the use of the adjective “aristocratic” as well. Burroughs’ obviously ascribes to the eugenics belief that poverty, etc. are a personal traits and that aristocrats remain aristocrats because of breeding and good genetics. We’ll discuss this more in the 80’s-90’s doorstopper era, as well. A similar worldview is implicit in characters like Sparhawk from Eddings’ Elenium series, even, to a certain extent, the noble families of the seven kingdoms in A Song of Ice and Fire, though I think Martin is doing more deconstruction.

Also, counterpoint: the Hapsburgs.

This is just a selection, by the way. I’ve got an ebook full of highlighted passages and comments, which range from “Jesus, Burroughs!” to “Century old incel catnip.”

Speaking of, just as an aside, there is a WHOLE series of books to be written on Tarzan and misogyny. When Tarzan becomes king of the Mangani apes and dispenses judgement, he orders one ape to “give up” a daughter and another to pay better attention to her “wifely duties.” That’s the entirety of Tarzan's policymaking.

Tarzan also, quote, “did what no red-blooded man needs lessons in doing.” Apparently thematic passionate kissing is also a genetic gift of the English.

Tarzan’s letter to Jane, which, in whatever vestiges of fairness I have left, he doesn’t actually send, reads, in part:

I am Tarzan of the Apes. I am yours. I want you. You are mine. We live here together always in my house.

Which is probably also where the “Me Tarzan, You Jane” speech pattern comes from in later TV and movie adaptations. Not to mention that, apparently, in Burroughs’ worldview, reason is all well and good until it’s time to ravage a woman that you just won through a physical contest with another male. Anyway, we’ll have ample opportunity to discuss misogyny in future texts.

So, Tarzan was and is a eugenics fantasy, along with being a profoundly racist novel. An academic paper from 2001 calls Tarzan of the Apes an “epic of eugenic triumph.” Tarzan of the Apes – and Burroughs larger catalogue – are literature profoundly motivated by a belief in the power of heredity to create a superior race. In this case, the British aristocracy. Which is certainly an opinion.

Racism and eugenics fundamentally motivate Burroughs’ catalogue as a whole, similar to how racial anxiety motivated much of Lovecraft’s work. You find eugenics themes in the Barsoom novels (John Carter was a Confederate, after all). And, Burroughs’ Lost on Venus is just some disgusting stuff. The main society that the protagonist discovers murders “social misfits” as a matter of state policy, and, at one point, the protagonist offers himself to be killed to preserve the eugenic eutopia. Seriously, Lost on Venus, which was written in 1933, more than 20 years after Tarzan of the Apes, is just really disturbing stuff. Even the Pellucidar series has quite a bit of racist themes.

Let's discuss how Burroughs was an early adopter of eugenics. Tarzan of the Apes was originally serialized in 1912 and published in book form in 1914. The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness, a famous and influential piece of fraudulent pseudoscience that had a major influence on the eugenics movement, was published in 1912, so after the initial writing and publication of Tarzan of the Apes. The Passing of the Great Race, another milestone and landmark book on eugenics, wasn’t published until 1916. Eugenics ideas certainly weren’t new in the early 20th century – Francis Galton coined the term to describe his research in 1883 – but Burroughs certainly was an early author who helped drag these ideas into popular fiction and fantasy fiction in particular.

The TL;DR version is that Burroughs was a racist that buttered up his racism with pseudoscience. Dude is arguably as bad (or worse) than Lovecraft and catches far less criticism for it, though that’s likely due more to current prominence than anything else.

The depth of Burroughs’ commitment to eugenics and racism isn’t even what I wanted to talk about, really. I did want to lay out some language from the text and other sources because you don’t have to dig too deep to find LOTS of folks who’ll come quickly to Burroughs’ defense, with the usual excuses. Such as, “everyone was racist back then.” Which:

That’s not an excuse.

No, they weren’t.

Ignores folks like, say, WEB DuBois, a contemporary.

Defenders also say things like, “he says nice things about some black characters too”, which ignores that the structure and motivating ideology of the stories is fundamentally racist. Genetic determinism, white savior, and basic, old-fashioned racism.

Burroughs: Believed in eugenics. Racist author. Jackass.

And, also, here’s the important part, hugely, hugely influential. Burroughs was a major touchstone for a lot of later authors. It’s here with Burroughs and the beginnings of pulp – a sub-genre that really comes to dominate the emerging fantasy genre in the 1920’s and 30’s – that the racial foundations of the fantasy genre, as a genre, are established. There are stories upon stories of lost cities, forgotten societies, etc. that populate the next couple of decades of fantasy and adventure fiction. Particularly after Burroughs’ success. Just like Lucas loved Flash Gordon and so we got Star Wars; a ton of authors read Burroughs and gave us stories inspired by him. You see his influence – and, it must be said, the general influence of how the prevailing culture thought about racial issues – with folks like Lovecraft (“Dagon” is a good example). Heinlein won’t shut up about Barsoom in his stories. Even A Voyage to Arcturus, published in 1920, 8 years after TOTA and which we’ll get to in a minute, shows a series of uniform cultures, with specific racial characteristics. Though, it admittedly does a much better job of creating individual characters within those races/cultures.

And this ties into discussions of more modern fantasy as well. Recent discussion around the fantasy genre has focused heavily on issues related to the treatment of race and representation in the genre. A lot of that discussion starts with Tolkien, who deserves some attention, certainly. LOTR has fantasy races – Men, Dwarfs, Orcs, Hobbits – that are fairly one dimensional, a generation or two after Burroughs was writing, a throwback to genetic determinism. An obvious example we’ll read later in the podcast is Dune. Paul Atraides is bred specifically to be the “chosen one”. Works out a little less well for him than Tarzan in the end, though. Even Star Wars is notorious for having single society planets. But Burroughs provides us with an early example of how these ideas – about racial uniformity, genetic determinism, white savior tropes, etc. – really burrowed their way into the foundations of the genre.

A lot of this isn’t necessarily true only of Burroughs. H.G. Wells deals with genetic manipulation in the 1896 novel The Island of Dr. Moreau, though with considerably more humility than Burroughs. But Burroughs much more prominently features these racial and eugenics ideas throughout his writing, and he was an enormously well-known and widely read author. Pretty much any fantasy or science fiction author of the middle 20th century is going to have read Burroughs. This idea that racial characteristics are specific to particular fantasy races or human societies in fantasy contexts – and all the problematic baggage those associations smuggle in with them – certainly owes a lot to the popularity of Burroughs and his characters John Carter and Tarzan/Lord Greystroke. No matter what anyone argues, these issues of racial representation in sci fi and fantasy are NOT a recent occurrence. They go right back to the roots of as the modern genre we know was coalescing. There’s more than a little path dependency here.

That’s…honestly way more than I wanted to talk about Tarzan of the Apes. I am skipping the positive aspects of the books: they are rollicking fun adventure reads, there is an action sequence – usually with Tarzan killing some sort of wild animal – almost every chapter. Unlike someone like Dunsany, the narrative moves quickly (except when Tarzan gets bogged down for chapters harassing the faceless black characters), the writing is crisp and wouldn’t be at all a difficult slog for a modern reader while being quite entertaining. Excluding, of course, the constant, stifling racism.

I have to think that, as a kid, I must have read the Great Illustrated Classics version of Tarzan or something. Great Illustrated Classics were those white cover, abridged, elementary level hardback versions of classic (read: out-of-copyright) books. Robinson Caruso, a lot of Dickens, Twain. That kind of thing. I know that’s how I was first introduced to stuff like King Solomon’s Mines (to which Tarzan owes a massive debt of influence) and The Time Machine.

However, my internet sleuthing doesn’t show that Tarzan was ever published as part of that series, so I’m just going to have to assume that 30-ish years ago I just read past a lot of this. Admittedly, the later sequels dial down the overt stuff a bit, but I really wasn’t prepared for the depth of the racial and eugenics themes in the first book. That’s a privilege that comes with being a white kid reading books written in a racist society.

Honestly, there are times when I think some of this early fantasy/adventure fiction should come with a racial version of the Bechdel test. Something like:

The story has to include at least two white characters having a discussion where they don’t denigrate another race, fictional or otherwise.

Ultimately, I see no reason not to leave Burroughs and Tarzan (and John Carter and the rest of them) in the past. Apart from the racial and eugenics motivations, there isn’t as much left to Tarzan as you might hope. Its potboiler adventure fiction. It’s a top-tier example of the type, but once you’ve mined that appeal to adventurism, there’s not much below the surface except these eugenic themes of hierarchy and race. And I suspect that the reason all the attempts at updating the Tarzan character and story for a more modern era stumble is because they can’t dodge those very themes.

Honestly, the best modern adaptation of Tarzan is probably 1997’s George of the Jungle, the pre-Mummy Brendan Fraser Tarzan spoof, which basically spends 90 minutes mocking the very premise of the story. While the animated 1999 Disney film dealt with these issues by literally removing all black people from the story, ostensibly set (somewhere) in Africa.

Brendan Fraser is also a national treasure and master of physical comedy, by the way.

Tarzan of the Apes represents the ultimate artistic historical document: it’s useful as a historical resource and definitely a window on to some uncomfortable truths about the birth of the fantasy genre. It wouldn’t do to ignore it and its lasting influence, good and bad, but there’s also not much to recommend revisiting it for anything other than academic curiosity. A genre as expansive as fantasy shouldn’t be beholden to the racist ideas of a dead eugenicist.

To be continued...

Comments